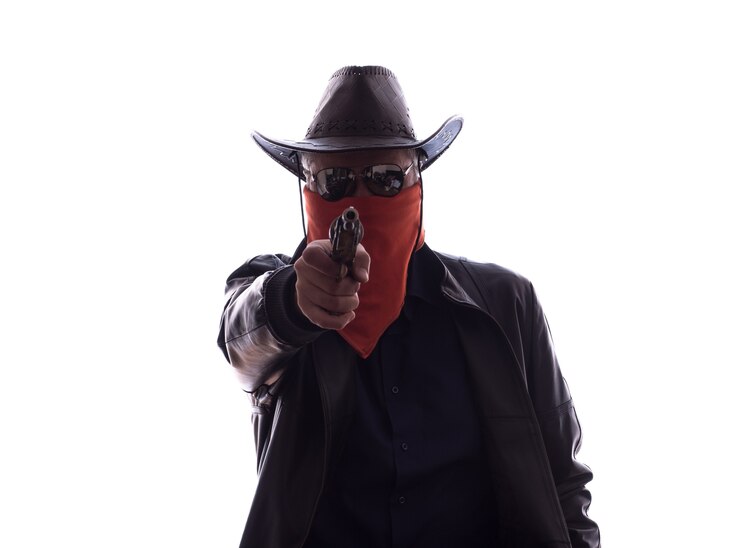

We sought to unpack what the “construction mafia” actually is and observed that the term is a mischaracterisation of its nebulous nature. The issue

We sought to unpack what the “construction mafia” actually is and observed that the term is a mischaracterisation of its nebulous nature.

The issue of extortionist rackets impacting construction projects has escalated to such a degree that Police Minister Senzo Mchunu has name-checked the construction mafia several times in public since his appointment in July 2024, making it a priority for the current administration.

Following the September 2023 article, clients have regularly asked us, “What can I proactively do to protect my business from the construction mafia?”. We have also been engaged by businesses that felt they had little choice but to accede to the construction mafia’s demands because the threat to bodily integrity and life, coupled with the cost of a work stoppage was too high. These businesses recognise the construction mafia for the blight they are and continue to seek ways to extricate themselves from their respective situations.

Ironically, it is well-intentioned legislation which has been hijacked by these bad actors.

The Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act (PPPFA), which applies to public procurement, was designed to promote economic transformation by seeking to ensure that 30% of public procurement contracts (see Regulation 9) were allocated to specific previously disadvantaged groups to empower these qualifying individuals, promote equity and drive socio-economic transformation.

While the objectives of the PPPFA are undeniably laudable, the construction mafia has sought to wilfully distort its objectives by demanding a 30% share of a project’s contract value. In our experience, the construction mafia has no regard for the distinction between private and public procurement, deliberately conflating the two to extend their reach into private sector developments. Considerations of extortion aside, the company that wins a tender also faces the added difficulty that Regulation 9 stipulates that the tenderer (to ensure that the 30% allocation criteria is met) should select a supplier from a list of suppliers provided by the state-owned entity that issued the tender. Construction mafia groups are, unsurprisingly, not usually on any supplier list.

The conundrum often faced by companies that win public tenders becomes quite apparent. They either have to withdraw their services (which in most instances they can ill afford to do and which would entail them repudiating their contracts and in so doing also exposing them to a potential damages claim), or they have to try and negotiate an outcome with these bad actors, which hopefully enables them to deliver the project on time, without risking the lives of their employees. The challenge is that while the companies in question are victims of unlawful behaviour, they are in turn acting unlawfully by engaging with an unlisted supplier. In addition, if the state-owned entity or branch of Government discovers that a non-listed entity has been sub-contracted, the winning bidders may run the risk of having their contract terminated and facing consequential damages claims.

The Prevention and Combatting of Corrupt Activities Act (PRECCA) complicates matters further because it provides that it is an offence for any person to accept gratification or bribe and to offer one. PRECCA also imposes a positive duty on any person in a position of authority to report corrupt acts (which is given a broad definition) where the monies involved exceed the sum of ZAR 100 000 (see section 34). Failure to do so gives rise to criminal liability, with penalties ranging from a fine to imprisonment of up to 10 years.

To aggravate matters, a company may also be exposed to an additional fine equal to five times the gratification or bribe which could prove ruinous. However, we see that coupled with the extortion, is a threat to the project and persons should the bad actors’ conduct be reported.

The Financial Intelligence Centre Act (FICA) also places an obligation on “accountable institutions” or “Reporting institutions” to report suspicious transactions or activities to the Financial Intelligence Centre. Typically, Section 29 of FICA requires any person who carries on a business or who is in charge of, or manages a business, to report suspicious or unusual transactions to the Financial Intelligence Centre, if there is knowledge or suspicion that the transaction involves proceeds of unlawful activities, terrorist financing, circumventing a duty under FICA, or funds linked to the financing of terrorist or related activities.

While construction companies themselves may not always be explicitly designated as accountable institutions, they often engage in large-scale transactions and are sometimes exposed to potential misuse, such as extortion payments or “facilitation fees” that may be associated with organised crime (eg the construction mafia). These factors can lead to situations where they need to be vigilant for suspicious transactions, especially where there is a risk of money laundering or organised criminal activities.

Read part two in the next issue of Concrete Connect where we will unpack the legal recourse available to businesses and potential practical interventions, including working with law enforcement agencies and communities.

COMMENTS